How SATA Reached Its Limit

SATA has been a central interface in consumer storage for nearly two decades, but its technical foundations now impose clear constraints. Originally created to replace the aging PATA interface, SATA was designed for spinning hard drives and the performance expectations of the early 2000s. Over time, SSDs dramatically surpassed the capabilities of this interface, revealing limits that have become increasingly problematic for both consumers and professionals.

One of the major boundaries is the maximum theoretical bandwidth of SATA III, capped at 6 Gb/s. In practice, this results in real-world speeds around 550 MB/s, which modern NAND flash can easily exceed. When SSD controllers evolved, they quickly reached a point where the interface itself became the bottleneck, preventing further progress. Even innovations like better caching, new flash types and more advanced wear-leveling algorithms could not bypass the interface limitation.

The issue goes beyond raw speed. SATA relies on the AHCI protocol, which was never optimized for parallel operations. AHCI offers a single command queue with 32 commands, compared to the thousands of queues available on modern NVMe implementations. This restricts the efficiency of contemporary SSD architectures, especially when managing small input-output operations in parallel, a common scenario in multitasking environments.

Another aspect is latency. While SATA significantly reduced the delays seen with old mechanical drives, it cannot compete with the extremely low latency achievable through PCIe-based connections. When applications like real-time analytics, game asset streaming or high-frequency data processing emerged, SATA drives were quickly outclassed, even when paired with otherwise powerful hardware.

These limitations collectively explain why SATA has reached a practical dead end. It still works as a reliable, affordable interface, but it no longer aligns with the direction storage technology is heading. As a result, manufacturers and users have naturally shifted toward other interfaces that better match current performance expectations.

NVMe and PCIe: The New Performance Standard

The shift away from SATA is largely driven by the rise of NVMe and PCIe, which provide the foundation for modern storage performance. NVMe was designed from the ground up for solid-state drives, enabling hardware to operate at its full potential rather than being restricted by legacy protocols. With its ability to take advantage of parallelism and high bandwidth, NVMe has become the de facto standard for high-speed storage solutions.

PCIe lanes offer vastly superior throughput compared to SATA. Even older PCIe 3.0 x4 SSDs can exceed 3,000 MB/s, while newer PCIe 4.0 and PCIe 5.0 models push speeds far beyond what the SATA interface could ever deliver. This makes PCIe-based drives game-changing not only for enthusiasts but also for professionals working with heavy data workloads. Activities like large-scale content creation, virtualization and AI dataset management all benefit significantly from NVMe-based storage.

The protocol also brings a more efficient command structure. Instead of the single-queue design of AHCI, NVMe supports up to 65,535 queues, each capable of handling up to 65,535 commands. This difference is substantial, especially in multitasking scenarios where SSDs must manage thousands of operations. NVMe handles this load more gracefully, allowing systems to maintain responsiveness even under stress.

The real strength of PCIe and NVMe lies in the combination of bandwidth, low latency and scalability. As new standards emerge, such as PCIe 6.0, storage manufacturers can continue to increase SSD performance without redesigning devices around outdated protocols. This makes NVMe not only a current solution but also a long-term foundation for future improvements.

Storage Trends Driving the Shift Away From SATA

The decline of SATA is not simply a matter of speed. Several industry trends have accelerated the migration toward more modern interfaces. These trends reflect changes in hardware design, software requirements and user expectations across both consumer and enterprise markets.

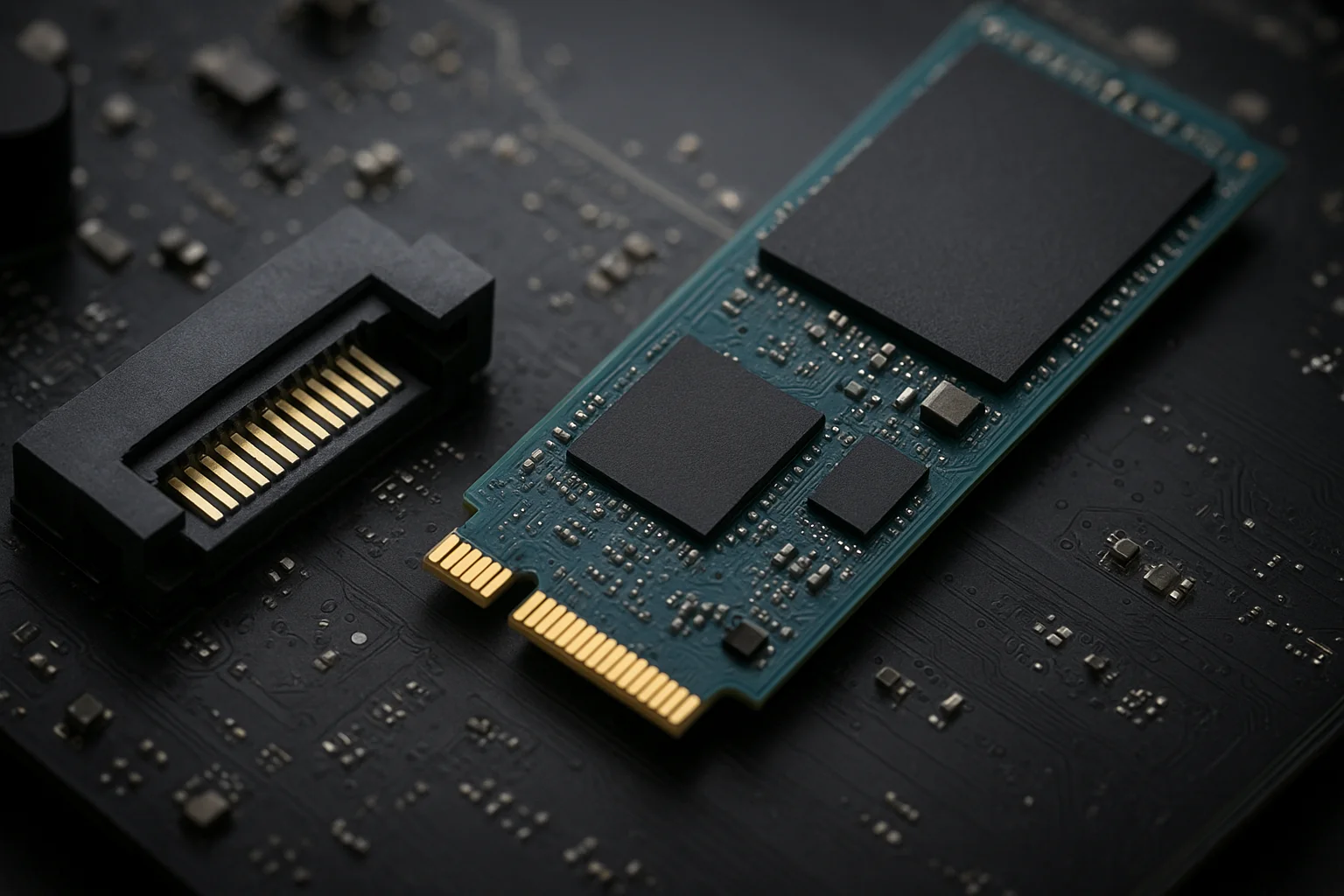

A key driver is the evolution of device form factors. Laptops have increasingly adopted compact designs that cannot accommodate traditional 2.5-inch drives. M.2 slots, which support NVMe SSDs directly through the motherboard, have become standard. This shift reduces cable clutter, saves internal space and simplifies thermal management. As a result, many new systems no longer include SATA ports at all, reinforcing the move away from the older interface.

Another important factor is the growing demand for faster data processing. Applications like 4K and 8K video editing, machine learning workflows, game installation optimization and large dataset manipulation all benefit greatly from NVMe performance levels. In many of these use cases, SATA drives create bottlenecks that slow down the entire workflow. Professionals who regularly handle intensive workloads have therefore adopted NVMe as a standard requirement rather than a performance luxury.

Price trends also play a major role. NVMe SSDs were initially much more expensive than SATA models, but the gap has narrowed considerably. Today, many mid-range NVMe drives are priced close to SATA SSDs while offering several times the performance. This reduced price difference diminishes the appeal of SATA for new builds, making it harder for manufacturers to justify continuing large-scale production of SATA-only products.

Because these trends overlap, the shift away from SATA is accelerating quickly. Manufacturers are focusing their efforts on NVMe models, and even entry-level systems are increasingly adopting M.2 slots as the primary storage interface.

What This Transition Means for Consumers and Enterprises

The practical impact of the end of SATA depends on your use case. For many consumers, transitioning to NVMe offers immediate benefits. Systems boot faster, software launches more quickly and multitasking becomes smoother. Even activities like game loading times or transferring large files see significant improvements. Users upgrading from HDDs or older SATA SSDs often experience the most dramatic gains with NVMe.

To help compare these practical differences, the table below summarizes the typical characteristics of SATA SSDs versus NVMe SSDs. This table is based on commonly observed performance and latency ranges rather than specific product models.

| Characteristic | SATA SSD | NVMe SSD |

|---|---|---|

| Typical throughput | 400 to 550 MB/s | 2,500 to 7,000 MB/s |

| Protocol efficiency | AHCI with limited parallelism | Optimized NVMe queues |

| Latency | Higher due to controller design | Very low, ideal for high IOPS tasks |

| Form factors | 2.5-inch | M.2 or PCIe add-in cards |

| Use cases | Basic upgrades, budget builds | Performance systems, professional workflows |

Enterprises also face important implications. As servers increasingly rely on NVMe drives, data centers gain faster access to databases, virtualization storage pools and containerized workloads. This helps reduce overhead and enables better resource utilization. The adoption of NVMe over Fabrics extends these benefits over networked environments, creating faster and more scalable infrastructures.

However, the shift away from SATA also requires planning. Older systems that rely on SATA backplanes may need adapters or complete replacements to support NVMe storage. Enterprises with large fleets of servers must evaluate the cost and timing of such transitions. Still, most organizations view the performance gains as well worth the investment, and many have already begun incorporating NVMe into both primary and secondary storage tiers.

The Future of Storage Interfaces Beyond NVMe

With the decline of SATA now underway, attention naturally turns to what comes next. NVMe will remain dominant for some time, but several developments indicate where the storage industry may be heading. One promising direction is the continued evolution of PCIe standards. PCIe 5.0 SSDs are already entering the mainstream, and PCIe 6.0 promises even higher throughput, making it possible to create drives that exceed current performance limitations.

Another emerging trend is the rise of CXL, a new interface designed to unify memory and storage access. While still early in its adoption, CXL could allow more flexible configurations where SSDs behave more like extensions of system memory. This approach has significant potential in fields such as AI, large-scale computing and cloud infrastructure, where reducing memory bottlenecks is increasingly important.

At the same time, storage manufacturers are exploring new types of NAND and even entirely new memory technologies. Although these innovations do not directly replace the NVMe protocol, they will influence how future drives are designed and how much performance can be extracted from upcoming interfaces. Some technologies may require further protocol enhancements or entirely new approaches to maximize efficiency.

While SATA still has a place in legacy systems and certain budget builds, the industry focus is clearly shifting toward more advanced interfaces capable of supporting next-generation workloads. Understanding these future developments helps users and organizations prepare for what comes after NVMe and anticipate the changing landscape of high-performance storage.